The restaurant industry isn’t easy. Roughly one in three restaurants fail within the first year of opening, with 80% closing within five years. Factor in the 2008 recession, the recent pandemic, and various other hurdles, and it’s pretty impressive that any restaurant going on a decade in New York City is still standing. Blue Ribbon Brasserie is celebrating that threefold, having recently marked the 30-year anniversary of the restaurant that launched the national Blue Ribbon restaurant group.

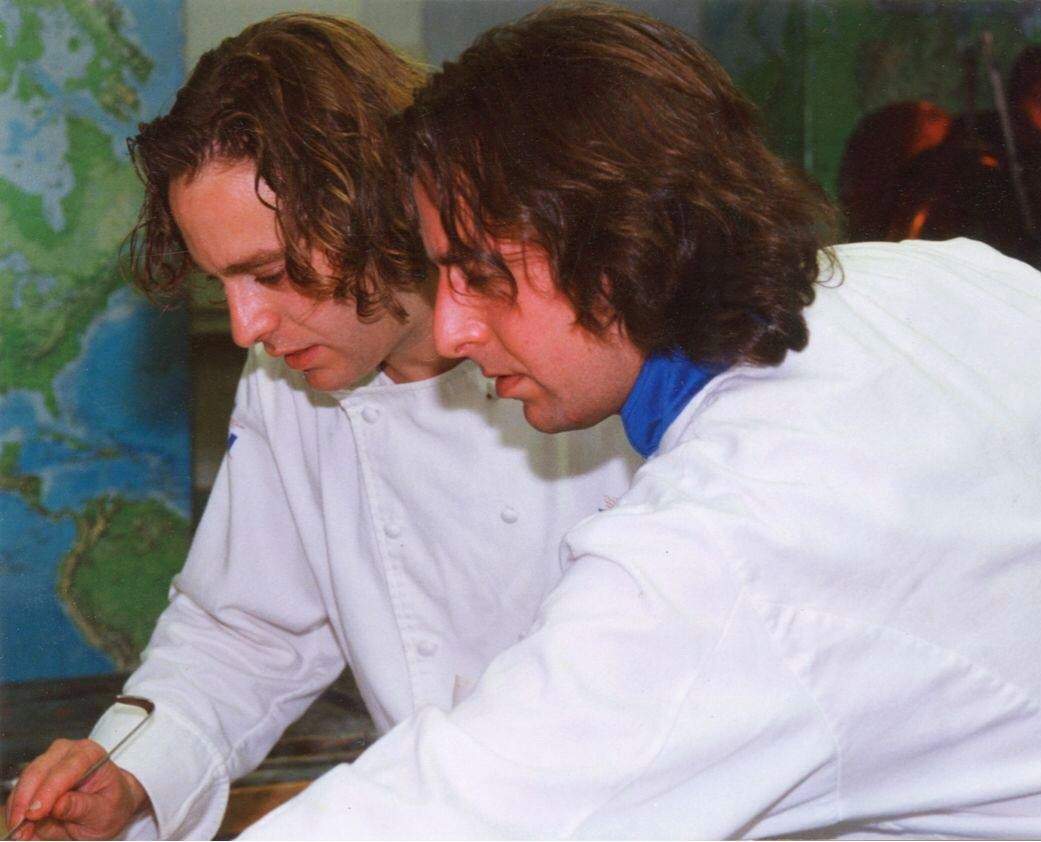

Brothers Bruce and Eric Bromberg, both Le Cordon Bleu graduates, debuted the Parisian-style brasserie on November 3, 1992, when few such spots existed in the city. Soon after, the restaurant became a staple for top American chefs, created dishes that have endured for decades, and helped the Brombergs establish a culinary empire with several restaurants across the country.

“My older brother Eric and I grew up in a very food-focused house,” Bruce Bromburg says, sitting in Pescador, Blue Ribbon’s newest restaurant, which will soon open in Boston. The siblings grew up in a “culinary Jewish” household, according to Bromberg, where holidays were celebrated via food and vacations were spent in search of new and exciting dishes. When Eric graduated college, he moved to Paris to attend Le Cordon Bleu, and Bruce followed in his footsteps five years later.

While Bruce was still in France, Eric worked in Sag Harbor and eventually opened a restaurant with a business partner in SoHo, always keeping an eye out for a space that would function as the brothers’ own. And then, armed with an excellent culinary education but a sparse resume, Bruce got the call from his older brother. “He said, come back, I found it. 97 Sullivan Street… And that was the beginning of Blue Ribbon.”

A go-to destination for chefs

“We didn’t think about the menu as much as what type of environment we wanted to create,” Bromberg says of opening Blue Ribbon Brasserie. They’d both experienced oppressive restaurants in their culinary education and careers and wanted to create a positive environment for customers and staff. “That’s been the focus for 30 years, making a positive workplace,” Bromberg says. And with that principle, the menu came to life.

They created dishes based on their childhood experiences, travels, and foods that had the most impact on their lives. Paella, matzo ball soup, roasted bone marrow, foie gras, and oysters on the half shell resonated the most. “It’s eclectic, but makes sense,” Bromberg says. The restaurant was envisioned like a Parisian brasserie, not too fancy, not too casual, and open until the wee hours of the morning for restaurant workers to indulge in once they clocked out at midnight.

“We did all these crazy things, out of the box of what an NYC restaurant looked like in the early 1990s,” Bromberg says, noting that restaurants either leaned toward upscale and expensive, or more casual diner-style venues. “It was a rebellion,” he says. “We wanted to be more for the neighborhood. In the city that never sleeps, why couldn’t you dine after midnight?”

A few months of empty seats were the last time the brothers would see the brasserie so quiet. Soon, local chefs and restaurateurs such as Charlie Trotter, Bobby Flay, and Drew Nieporent trickled in after their restaurants closed for the night, often bringing colleagues and staff, to drink a nice bottle of wine alongside Blue Ribbon’s signature fried chicken. Daniel Boulud, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, and Tom Collichio soon followed. Some nights, each booth would represent a different restaurant group.

“Bit by bit the scene changed,” Bromberg recalls. “All of a sudden we were always packed at 2 am. It was an amazing time. We were learning. Restaurants were changing, chefs were starting to own restaurants. It was like a clubhouse and meeting room.”

A legendary dish that endured

Just as the brasserie became a go-to destination for local chefs, stories of Blue Ribbon’s fried chicken reached far and wide. “As my dad jokes, if he knew we’d be so well known for fried chicken, he could have saved a lot of money on Le Cordon Bleu,” Bromberg says. “But that training probably helped us.”

Fried chicken was an early menu item at Blue Ribbon Brasserie, reminiscent of fried chicken the brothers had delivered to their house via pickup truck. “It was unheard of for fine dining [restaurants],” Bromberg says of serving the dish at their restaurant. But the brothers were committed. However, coming up with a signature recipe proved challenging. Then, one night after prepping matzo balls and crème brûlée, leftover matzo meal and egg whites became the magic ingredients for Blue Ribbon’s star attraction.

“It was amazingly crisp and light fried chicken,” Bromberg says. The fried chicken remains a favorite 30 years on, and it propelled the brothers to open the standalone Blue Ribbon Fried Chicken on the Lower East Side.

Blue Ribbon makes eating sushi accessible

After a year in business, Blue Ribbon Brasserie was bursting at the seams. The brothers had never envisioned seating 300 diners between 4 pm to 4 am each night, especially in a 48-seat restaurant. The kitchen lacked enough space to stock dry goods, the wine fridges couldn’t accommodate all the bottles, and all the woes of Manhattan’s compactness were evident. They asked the landlord for more space, perhaps storage, but with the price of rent in SoHo, paying so much to keep ingredients nearby was exorbitant. The Brombergs considered using the small space next door to open a seafood restaurant to partner with fisherman friends from Long Island, but that never quite materialized.

“We got this idea of a sushi restaurant,” Bromberg says. This was 1994, when most of Manhattan’s sushi spots were casual, all-you-can-eat maki joints, or super high-end spots, where the brothers never felt quite comfortable. The $700 check for excellent sushi wasn’t realistic, or satisfying.

“We wanted to let customers feel comfortable,” Bromberg says. “We didn’t know much about sushi, so we ate all over NYC, getting ideas and trying to meet a chef.” Then, after an especially pricey and disappointing meal, the brothers passed a small sushi joint on Lexington Avenue and 27th Street. They sat down and bit into a spicy scallop hand roll prepared by the only chef working in the restaurant, serving just one other customer. “It was amazing; that was it,” Bromberg says.

From there, they brought in friends and colleagues before working up the nerve to ask the chef and owner, Toshi Ueki, if he wanted to partner on Blue Ribbon Sushi. The restaurant opened on November 3, 1994.

“It was a very difficult first year; few Americans owned sushi restaurants,” Bromberg says. And though Blue Ribbon Brasserie was still thriving, no one was intrigued by the sibling sushi restaurant. In fact, the brothers were known as food media’s token Jewish chefs, Bromberg recalls; they’d get quoted in newspapers and share recipes for Jewish holidays, but were far from Japanese food experts, despite what Ueki brought to the table.

And then, New York Times restaurant critic Ruth Reichl rated Blue Ribbon Sushi two stars, in a review titled, “Sushi for Novices, Without Loss of Face.” She raved about how quality sushi could be accessible, and the reservation-free restaurant (at that time) was bustling from there. Since, countless accessible sushi restaurants have opened across NYC, with Blue Ribbon Sushi expanding to several locations throughout Manhattan.

A national expansion

“We never dreamed of growing to this level or even expanding up to Midtown. South of Houston Street was our world,” Bromberg says. But as opportunities presented themselves, Blue Ribbon Restaurant Group kept expanding.

In 2010, the brothers opened their first restaurant outside of New York, Blue Ribbon Brasserie at the Cosmopolitan Las Vegas. Apart from opening individual restaurants, Blue Ribbon is also now the in-house food provider for Brooklyn Bowl, offering finger foods like their fried chicken, French bread pizza, and more at locations in New York, Philadelphia, Nashville, and Las Vegas. In total, Blue ribbon operates 21 restaurants across the country.

Now, on the eve of opening Boston’s Pescador, Bromberg doesn’t know what’s next. He hopes all the restaurants make it to 30 years and beyond.

“We try to make everlasting restaurants that people love,” Bromberg says.“Thirty years seeing what Blue Ribbon has done for the culinary community is incredibly satisfying and inspired us to continue. It’s been an amazing ride.”

Melissa Kravitz Hoeffner is a writer based in Brooklyn, where she lives with her wife and rescue dog. You can follow her on Instagram @melissabethk and Twitter @melissabethk